Street Art Goes Inside at UMOCA

Part of the thought process that Jared Steffenson, curator of exhibitions at UMOCA, engaged in when developing the museum’s current ALL WALL exhibition was considering where and how many people experience art for the first time. “I grew up in the Bay Area where I spent a lot of time skateboarding in places with graffiti or street art, which is how I think many people get their first exposure to art,” he says. “Murals are both very democratized and, particularly recently, reflect what is going on in a community at a given time. And so, a couple of years ago, when we were coming up with exhibitions for 2021, which is UMOCA’s ninetieth anniversary, part of our goal was to create exhibitions that are less about us and more about the community. A mural exhibition was one of the ideas that quickly rose to the top.”

Other than size and encouragement to use the opportunity to try something new, Steffenson gave the artists he assembled for ALL WALL complete freedom to design whatever they wanted. The resulting exhibition, with each mural on display side-by-side in UMOCA’s main gallery—similar to how murals often appear on the street—spans a beautifully balanced variety of aesthetics and styles and, as is endemic to much contemporary art, includes pieces created to communicate a specific idea or message to the viewer.

Upon first glance of the mural Doo yá’át’éehii hólóo nisi ts’ídá yá’át’éeh hodooleego t’éí nitsihwiildeel, created for ALL WALL by Denae Shanidiin and Chuck Landvatter, it’s clear that, through images including children, text and a man clad in a suit and tie reading from a book, Shanidiin and Landvatter have something to say. Their mural’s central image is a portrait of Arthur Vivian Watkins, a two-term Republican Utah Senator who served from 1947 to 1959. During his time in the Senate, Watkins pushed for termination of federal recognition of American Indian tribes and assimilation of indigenous peoples into mainstream Euro-American society.

One of the tools Watkins’ used to accomplish the latter goal was Indian Reform Schools, or boarding schools where indigenous children were forced to give up their languages and religion and, as we now know, were rife with violence and abuse. More than 350 such schools existed across the U.S. at one time, including four in Utah. The remainder of the images that appear within the mural—a group of indigenous children with their eyes redacted “to protect the identities of those who have suffered trauma,” Shanidiin says; two indigenous girls, one on horseback; and an aerial image of a town—are historic photographs taken at the Intermountain Indian School, which operated in Brigham City from 1949 to 1984, that Shanidiin and Landvatter licensed for use from the Box Elder Museum of Art, History and Nature.

Shanidiin connection to the Intermountain Indian School is personal: relatives from both sides of her family were sent there as children. But with her Diné and Korean ancestry, she also feels a greater connection with the greater population of indigenous people who have suffered within these residential facilities across North America. Her family’s experience coupled with the horrifying discovery earlier this year of human remains on the grounds of an Indian reform school in Canada compelled her to create a mural for ALL WALL exploring this extremely painful and almost universal chapter in indigenous peoples’ pasts. “It’s an ugly history that happened not that long ago,” Shanidiin says. “It felt appropriate to take up that space with the truth about what happened at those boarding schools and how our people continue to carry that trauma with them today.” (Note: On August 23, 2021, The Salt Lake Tribune reported that Utah State University plans to use ground-penetrating radar to investigate 150 acres surrounding the former site of an indigenous boarding school in Panguitch in search of the bodies of at least 12 children believed to be buried there.)

Landvatter explained that his part in Doo yá’át’éehii hólóo nisi ts’ídá yá’át’éeh hodooleego t’éí nitsihwiildeel was, as an experienced muralist, to help transfer Shanidiin’s concept to a wall-sized piece, drawing specifically on his skill as a figure artist to paint the image of Watkins. “Art is usually defined by the upper echelons of society and many critics and other artists don’t endorse murals or street art as real art,” Landvatter says. “It’s exciting through ALL WALL and other efforts to see it become part of the conversation in a more serious way.”

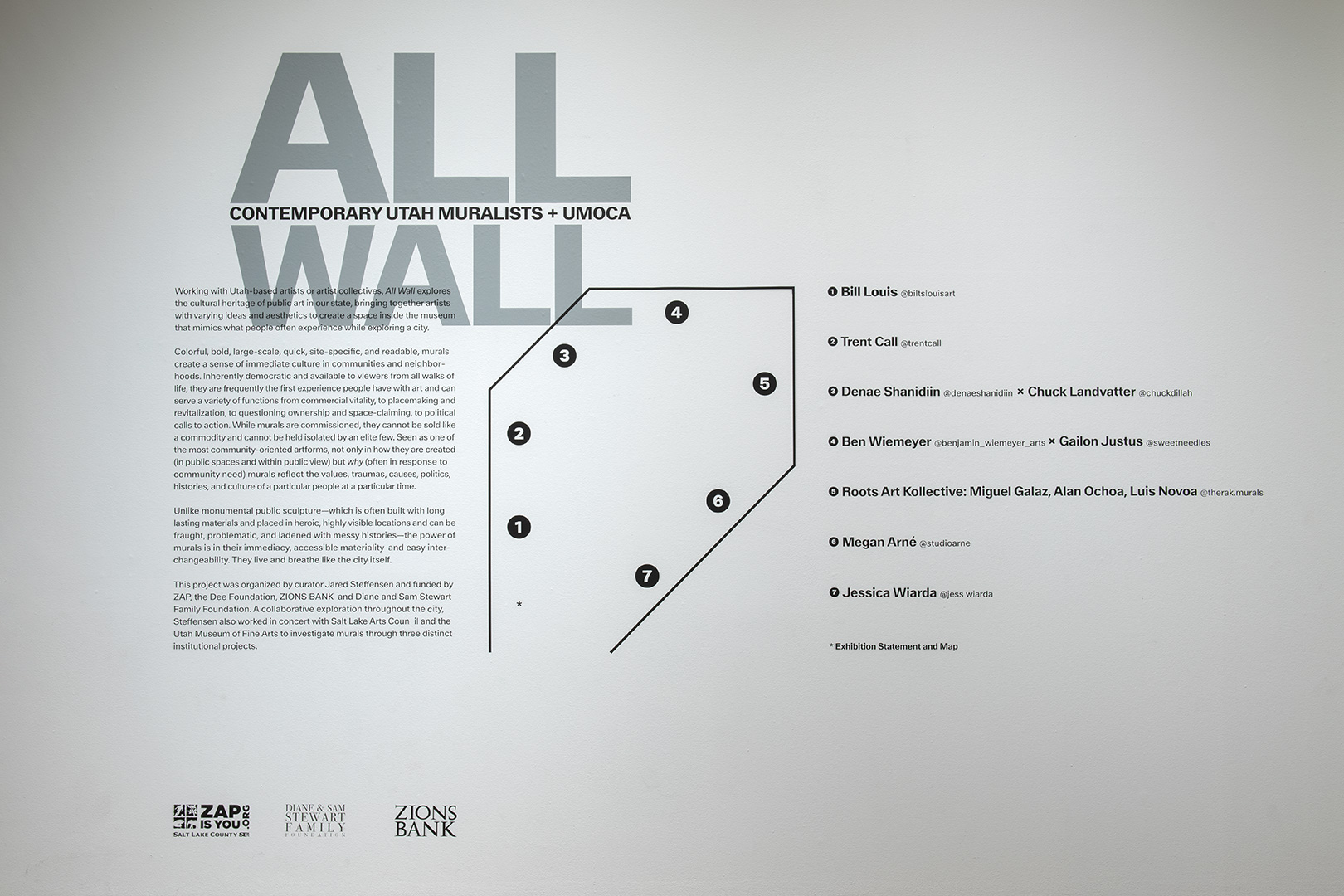

The other mural artists Steffenson invited to participate in ALL WALL include Bill Louis, a Polynesian (Tongan/Fijian) urban abstract artist; a collaboration between Ben Wiemeyer, a graffiti artist and tattoo artist Gailon Justus; well-known Salt Lake City muralist, illustrator and fine art painter Trent Call; a collab between Miguel Galaz, Alan Ochoa and Luis Novoa, which they call the Roots Art Kollective; muralist and installation artist Megan Arné; and Jessica Wiarda, an illustrator of Hopi/Tewa and white descent.

ALL WALL will remain on display in UMOCA’s Main Gallery presented by Diane and Sam Stewart though January 8, 2022 after which these seven artworks will be painted over in preparation for another exhibition.

“Any mural you make in the world is precarious, which is a part of making murals you just have to accept,” Call says. “But I also like how their temporary nature ensures that they really don’t belong to anyone.”

Not only are murals having a museum-level moment at UMOCA, but, starting next month, will grace the interior walls of the Utah Museum of Fine Art (on the campus of the University of Utah) as well. On September 25, 2021, the UMFA opens 2020: From Here on Out, a mural project curated in part by the Roots Art Kollective that asked muralists to consider how they experienced the last crazy year and how they think it will impact our future.

Downtown Salt Lake City’s streets are, of course, alive with dozens of murals as well. You can enjoy a self-guided tour of downtown’s diverse street art by downloading THE BLOCKS Mural Trail app.

Written by Melissa Fields